Page 337 - TNFlipTest

P. 337

Toronto Notes 2019 Common Presenting Problems

Family Medicine FM39

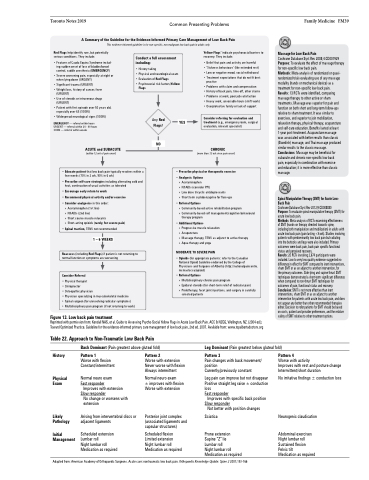

A Summary of the Guideline for the Evidence-Informed Primary Care Management of Low Back Pain

This evidence-informed guideline is for non-specific, non-malignant low back pain in adults only

Red Flags help identify rare, but potentially serious conditions. They include:

• Features of Cauda Equina Syndrome includ- ing sudden onset of loss of bladder/bowel control, saddle anesthesia (EMERGENCY)

• Severe worsening pain, especially at night or when lying down (URGENT)

• Significant trauma (URGENT)

• Weight loss, history of cancer, fever

(URGENT)

• Use of steroids or intravenous drugs

(URGENT)

• Patient with first episode over 50 years old,

especially over 65 (SOON)

• Widespread neurological signs (SOON)

EMERGENCY — referral within hours URGENT — referral within 24 - 48 hours SOON — referral within weeks

ACUTE and SUBACUTE

(within 12 wk of pain onset)

Conduct a full assessment including:

• History taking

• Physical and neurological exam • Evaluation of Red Flags

• Psychosocial risk factors/Yellow

Yellow Flags* indicate psychosocial barriers to recovery. They include:

• Belief that pain and activity are harmful

• ‘Sickness behaviours’ (like extended rest) • Low or negative mood, social withdrawal • Treatment expectations that do not fit best

practice

• Problems with claim and compensation

• History of back pain, time-off, other claims • Problems at work, poor job satisfaction

• Heavy work, unsociable hours (shift work) • Overprotective family or lack of support

Consider referring for evaluation and treatment (e.g., emergency room, surgical evaluation, relevant specialist)

CHRONIC

(more than 12 wk since pain onset)

Massage for Low Back Pain

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;4:CD001929 Purpose: To evaluate the effect of massage therapy for non-specific low back pain.

Methods: Meta-analysis of randomized or quasi- randomized trials evaluating use of any massage modality (hands or mechanical device) as a treatment for non-specific low back pain.

Results: 13 RCTs were identified, comparing massage therapy to other active or sham treatments. Massage was superior for pain and function on both short and long-term follow-ups relative to sham treatment. It was similar to exercises, and superior to join mobilization, relaxation therapy, physical therapy, acupuncture and self-care education. Benefits lasted at least 1-year post-treatment. Acupuncture massage

was associated with better results than classic (Swedish) massage, and Thai massage produced similar results to the classic massage. Conclusions: Massage may be beneficial for subacute and chronic non-specific low back

pain, especially in combination with exercise

and education; it is more effective than classic massage.

Spinal Manipulative Therapy (SMT) for Acute Low- Back Pain

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;9:CD008880

Purpose: To evaluate spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) for acute low back pain.

Methods: Meta-analysis of RCTs examining effectiveness of SMT (hands-on therapy directed towards spine, including both manipulation and mobilization) in adults with acute low back pain (pain lasting <6 wk). Studies involving patients with predominantly low back pain but radiating into the buttocks and legs were also included. Primary outcomes were back pain, back-pain specific functional status and perceived recovery.

Results: 20 RCTs involving 2,674 participants were included. Low to very low quality evidence suggested no difference in effect for SMT compared to inert interventions, sham SMT or as an adjunct to another intervention, for

the primary outcomes. Side-lying and supine thrust SMT techniques demonstrated a short-term significant difference when compared to non-thrust SMT techniques for outcomes of pain, functional status and recovery. Conclusion: SMT is not more effective than inert interventions, sham SMT or as an adjunct to another intervention for patients with acute low back pain, and does not appear any better than other recommended therapies either. Decision to refer patients for SMT should be based on costs, patient and provider preferences, and the relative safety of SMT relative to other treatment options.

Flags

Any Red Flags?

NO

YES

• Educate patient that low back pain typically resolves within a few weeks (70% in 2 wk, 90% in 6 wk)

• Prescribe self-care strategies including alternating cold and heat, continuation of usual activities as tolerated

• Encourage early return to work

• Recommend physical activity and/or exercise • Consider analgesics in this order:

» Acetaminophen (1st line)

» NSAIDs (2nd line)

» Short course muscle relaxants

» Short-acting opioids (rarely, for severe pain)

• Spinal traction, TENS not recommended 1 – 6 WEEKS

Reassess (including Red Flags) if patient is not returning to normal function or symptoms are worsening

Consider Referral

• Physical therapist

• Chiropractor

• Osteopathic physician

• Physician specializing in musculoskeletal medicine

• Spinal surgeon (for unresolving radicular symptoms)

• Multidisciplinary pain program (if not returning to work)

Figure 13. Low back pain treatment

• Prescribe physical or therapeutic exercise • Analgesic Options

» Acetaminophen

» NSAIDs (consider PPI)

» Low dose tricyclic antidepressants

» Short term cyclobenzaprine for flare-ups

• Referral Options

» Community-based active rehabilitation program

» Community-based self management/cognitive behavioural

therapy program

• Additional Options

» Progressive muscle relaxation

» Acupuncture

» Massage therapy, TENS as adjunct to active therapy

» Aqua therapy and yoga

MODERATE TO SEVERE PAIN

• Opioids (for appropriate patients: refer to the Canadian National Opioid Guideline endorsed by the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta) (http://nationalpaincentre. mcmaster.ca/opioid)

• Referral Options

» Multidisciplinary chronic pain program

» Epidural steroids (for short-term relief of radicular pain)

» Prolotherapy, facet joint injections, and surgery in carefully

selected patients

Reprinted with permission from: Kendall NAS, et al. Guide to Assessing Psycho-Social Yellow Flags in Acute Low Back Pain. ACC & NZGG, Wellington, NZ. (2004 ed.); Toward Optimized Practice. Guideline for the evidence-informed primary care management of low back pain, 2nd ed. 2007. Available from: www.topalbertadoctors.org

Table 22. Approach to Non-Traumatic Low Back Pain

Back Dominant (Pain greatest above gluteal fold)

Leg Dominant (Pain greatest below gluteal fold)

History

Physical Exam

Likely Pathology

Initial Management

Pattern 1

Worse with flexion Constant/intermittent

Normal neuro exam Fast responder

Improves with extension Slow responder

No change or worsens with extension

Arising from intervertebral discs or adjacent ligaments

Scheduled extension Lumbar roll

Night lumbar roll Medication as required

Pattern 2

Worse with extension Never worse with flexion Always intermittent

Normal neuro exam

± improves with flexion Worse with extension

Posterior joint complex (associated ligaments and capsular structures)

Scheduled flexion Limited extension Night lumbar roll Medication as required

Pattern 3

Pain changes with back movement/ position

Currently/previously constant

Leg pain can improve but not disappear Positive straight leg raise ± conduction loss

Fast responder

Improves with specific back position Slow responder

Not better with position changes Sciatica

Prone extension Supine “Z” lie

Lumbar roll

Night lumbar roll Medication as required

Pattern 4

Worse with activity

Improves with rest and posture change Intermittent/short duration

No irritative findings ± conduction loss

Neurogenic claudication

Abdominal exercises Night lumbar roll Sustained flexion Pelvic tilt

Medication as required

Adapted from: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Acute care: nontraumatic low back pain. Orthopaedic Knowledge Update: Spine 2 2001;153-166